Tony Knebworth was an early member of 601 Squadron and a very well-liked pilot. Tragically he was killed while practicing for an air demonstration.

The following is taken from the website hertsmemories.org.uk and used with permission by the family & Knebworth House.

Antony was born on 13 May 1903, the son of Victor and Pamela Lytton and died in 1933 in an air crash in Hendon. He was frequently separated from his parents throughout his short life, whilst at school, university and then serving in politics, so left a huge number of letters. His father described him as “a supremely good letter writer, and his letters gave expression to all the changing moods through which he passed”.

Following his death, his father wrote a biography of his life, “a tale of sustained health, of progressive achievement, of vitality unimpaired, of courage undaunted and high spirits that never flagged.” We are therefore taking extracts from this book, following Antony’s life and Henry Lytton Cobbold, Great Nephew of Antony, is reading the letters.

Further information about the family can be obtained on their website at Knebworth House.

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON: CHAPTER I

Childhood and West Downs

By his father, the Earl of Lytton

The first four years of Antony’s life were spent in London, at 32 Queen Anne’s Gate, the house where he was born. His sister Hermione ( the present Lord Cobbold’s mother) was born in the same house in 1905. In 1906 they moved to the Manor House at Knebworth, and to Knebworth House in 1908. In 1911, at the coronation of King George, Antony was Page to Prince Arthur of Connaught and announced the news in a letter

“Isn’t it jolly? I am going to be a page and to Prince Arthur. My first historical event June the 22nd 1911. Do tell me what I have to do and what I shall have to wear?”

After going to Clarence House to be photographed, he returned in the royal carriage. A royal footman opened the door and little Antony stepped out, very calm and erect, with a beaming rosy face, beautifully dressed in smartest scarlet livery, with sword and plumed hat (now on display at Knebworth House).

In 1913, Antony left home to start school, West Downs in Winchester. One of his first postcards home, he wrote

“I am just going out to play footer. I am getting on very well I have not made many enimes, much love”

He wrote frequently, not only the regulation Sunday letter but several times during the week, telling of his friendships and his activities. Here is an example of his descriptive power

“What do you think happened on Thursday? Just at the beginning of the first brake we saw an aeroplane flying very close, and it went round and round in a circle getting nearer the ground every time. At last in descended out of sight down the bank, and the whole school ran after it, over the fence, over the road, down to the valleys of the golf course, till we same in sight of it, a big yellow thing looking like a boat upside down. When we came up with it we found it smashed up. It was an army one, and the man had come down to look at his map and was running along on the ground when he saw a bunker and pulled the leaver to send it into the air, it did not act and he was wrecked. His wheels were smashed and the screw broke in two, he had a narrow escape with his life, but I touched it for the first time”

During 1913, Antony first had chicken pox, then had an operation for appendicitis. As Knebworth House was being rented out to the Grand Duke Michael, brother of the Czar of Russia, Antony spent his convalescence in London, before returning to school in 1914. The Grand Duke returned to Russia at the outbreak of the First World War. His mother organised a hospital for wounded soldiers in London and Antony wrote to her saying

“How is the hospital? Can I be of any use as messenger or anything connected with the hospital as scout in the holidays?”

“It has been snowing most of today and we have only been able to get out once to have a little game of chivy. Captain Rowland Phillips has been here today giving us some lovely tips. He is a Commissioner for all school troops. He is telling us some lovely yarns about the front now. It is awfully exciting. He has been telling us some glorious indoor games. He is talking all about bombing, glorious! We have got a God in the room, it is great fun. He is talking so well that he makes you think you are in the trenches. Good-bye.”

On the 18th March 1916 he came to London for the day, and his letter describing his return journey was characteristically vivid:

“… Directly the train started I tried to do that puzzle and did not even look up to say good-bye because I did not want to feel miserabler than I could help. Then I just opened the parcels, so as I could see what was inside them – there was jam sandwiches, cake, 2 plums, a bottle of milt, 4 caramels and lots of toffee. Then I started off and fairly well gorged, looking at the Illustrated War News in between the bites…..”

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON: CHAPTER II

Eton: War Years 1916-1918

By his father the Earl of Lytton

Antony started at Eton in 1916 and his first two years at the school were spent while the country was in the grip of war – fires were few and far between, and food greatly restricted. In his first letter home, he wrote

“I am radiantly happy here…. The food here is fine…. I adore this place, it is glorious. We haven’t done any work yet except a little history. We had sardines for tea and boiled eggs and cake. My bath has come. One only gets one can full of water and that fills it to about the depth of ½ an inch. There was early school this morning. It is bitterly cold and my hands and feet are icy. How I love this place. At least I do at present. We have the most wonderful teas ever known. We had two poached eggs each today which may amuse you. We have finished the Gentlemen’s Relish and the potted meat (which we can get for 8d a pot here) and the sardines which are very welcome. There are still loads of Fortnum & Mason caramels left. I didn’t know there were so many in the world. I have 52 every day, so does David, and Furze 42, and there are as many left as there were at the beginning! I am writing this in David’s room between prayers and supper….. I play short (sudden change of subject but I must write it before I forget). I have just finished an extra work. We have lots of spare time here – Prayer bell – there is goes. Goodnight, Antony.”

The correspondence between Antony and his mother, and his father, continued to reflect his enjoyment of life at Eton and by 1918 he exclaimed

“My God! What a place Eton is! There’s nothing like it in the world. You were quite right in say that it was worth being a boy for the sake of going to Eton. I am most radiantly happy”.

By Michaelmas Term of 1918 he had joined the Officers Training Corps, but the greatest event of that year was the signing of the Armistice in the November, and the dispersion of the war cloud which had overshadowed the whole of this school life. Victor, Earl Lytton, had been asked by Lord Beaverbrook to go to Paris as Commissioner of Propaganda involving him in discussing the terms of the armistice. Victor himself wrote to Antony saying

“We are all on tiptoe of excitement here, hourly awaiting the announcement that the Armistice has been signed. The situation in Germany is very desperate – a starving population in open revolution, and a beaten army in full flight. Before you receive this letter it will be all over. I wonder what form of rejoicing you will have at Eton. I think everyone will go mad with joy……..The punishment of the Germans will be terrible. The soldiers who for 4 years have exercised their brutal tyranny over the unfortunately French and Belgians are now being driven out with the execrations of the entire world ringing in their ears ,and for them there will be no home and no peace to return to for years to come. At first they will find hunger and revolution, and then they will have to submit to the occupation of their country by foreign troops until they have paid for all the wanton destruction they have caused. But it is always so in this world, with nations and with individuals. The most pitiless judge is the Nemesis of one’s own acts”

At the same time, Antony was writing about his own experience of the armistice at Eton:

“I must write you an accurate account of everything that has happened here lately, because it is very thrilling….. On Monday 11 November. Everyone seemed to know that if the armistice was signed, fighting would stop at 11.10. I don’t know how everyone knew but they did, or thought they did. There were all sorts of rumours that the armistice had been signed, and we all agreed before 11.0 school that if Blacker led it we would all cheer at 11.10. Eleven fifteen came, and then Blacker got up and said ‘It is 10 minutes past 11, hip hurrah’, and no one backed him up……. When I came out of school I found a huge crowd assembled outside the school, and the headmaster stood on the steps and gave out, ‘French official wireless. All fighting ceased at 11’. There was a pause and then he went on, ‘There will be no parade or work this afternoon, and tomorrow will be a non dies’. Then Eton went mad and yelled themselves purple. First of all I went to tap and ate till my money ran out. Then I got hold of Frank Stacey, and we went down to Selling and Clifford and bought a flag about the size of a pocket handkerchief for 2/-. Led by Armitage and Shirley with a gong, we rushed all over Eton yelling. We stopped outside Chitty’s, and sang ‘God save the King’ with someone rolling a drum. I got hold of the lid of a tin and broke a bit of box on my fender, and beat it furiously. Finally Armitage got up on the steps outside Chapel and said ‘We’ve made enough row now lets go home’, and we all went….”

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON: CHAPTER III

Eton: After the war 1919-1921

By his father the Earl of Lytton

The great event for the summer of 1919 was the final conclusion of peace. Earlier in May, Antony had written

“Tell me all the news about Peace terms and people. The terms seem terrific to me in the Daily Mirror. I can’t think they’ll sign”

Then came the news of the scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow. On 23rd June his mother wrote :

“My mind is full of the German fleet. It’s the cleverest thing they have done yet, for after all the ships were ours, no longer theirs. What a disaster”, to which Antony replied

“I don’t agree with you about the German ships. I think that really it is the best possible thing that could have happened. We could hardly have claimed them, already having the largest Navy in the world, and we don’t really want them to go to France or Italy. Though it may not be the right thing to say, surely it suits us down to the ground, since it leaves us with far and away the largest Navy, and there is no county except America which could ever afford to build as big a one”.

When the Peace terms were finally signed, Antony wrote that they were going to have a torchlight procession and songs, a concert and a parade. He later described the celebrations in a letter….

“Oh, I feel an absolute wreck this morning, dead tired and awfully sleepy. We didn’t get to bed till after 12 last night. Our peace celebrations were great fun. We had the annual inspection in the morning, which I think was rather unnecessary, but once over we lined the streets for the Windsor procession of demobilised men. Then Ramsey got a scratch team against us in the afternoon, and gave us an awfully good tea, the only trouble being that it rained nearly all the time, but it was great fun and awfully good of Ramsey. We then had a sort of yelling sing-song in the school hall with ‘Katie’, ‘Smiles’ etc and ‘Auld Lang Syne’, and we screamed until we burst”.

Early in the Michaelmas school term he wrote to his mother “Do you mind if I learn boxing this half?…This half is perfect. I adore Eton and am very happy”. A few days later he wrote “Oh, I do love this place, and my friends, and life in general. There is a depressing sort of feeling on waking up in the morning – cold water, whole schoolday, dull all the afternoon. But when the evening comes, and one just lives, everything is too divine. I adore football, too, oh yes, I love it. I want to get very strong and well and in tremendous training – boxing and football. Oh, I am going to get so strong….”.

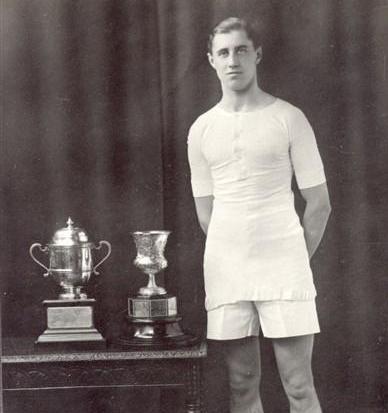

The following year, March 1920, following his success as a boxer, he wrote “… I have just won the ante-final of the Lightweight boxing against D Dawnay. I won the first bout last night, and tomorrow evening I have to fight the final against one Nettleton K S, a very slow, very heavy bruiser, a terrific hitter who I’m rather afraid of, bit if I keep my head and box well, I might beat him. Oh I can’t tell you what the joy of winning a fight is…..”

Before the end of school term in 1920, Antony’s thoughts started to turn to his future, “I had got two ideas, of which at present I am in favour of the latter:

(1) I go into the Diplomatic Service. I become the greatest Englishman in Europe, sworn by in 5 capitals, deified by the Hindoos, while Viceroy, and eventually Foreign Minister upholding every high-handed action of our agents all over nations, insulting America with impunity, with the whole world cowering at my feet. Then perhaps P.M. and a grave in Westminster Abbey, the biggest diplomat of the 20th century on a level with Palmerston and Bismark, and leaving England absolutely supreme in the world, with her hand in every pie, grasping, successful, feared and honourable.

(2) I feel that I might be all this and that I might be one of the biggest men that ever was, and yet I don’t really want to be. The baby side of my character is so predominant, and what I want to do is to go into a business, marry a divine wife, live in the country at a divine farm, keep animals, etc, and meanwhile pile up a pretty fair sum of money…….”

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER IV

Eton: In Pop – 1921-1922

By Ann Judge

The last year at Eton was a time of change and uncertainties for Antony. He couldn’t decide whether to leave early, possibly to spend a year in India with his father who had become the Governor of Bengal, or to complete his studies either at Oxford or Cambridge – another difficult decision.

He started the year ‘in Pop’ (an Eton term for Prefect), and then returned after Christmas, having decided to say goodbye to his parents who left for India in March 1922. Their parting was difficult to bear for all of them; Antony wrote

“I can never thank you and Daddy enough for giving me such a wonderful life and making me so very full of happiness. I only hope that in the time to come I shall be able to show myself worth of it all, and turn out a really grateful and good son to such a marvellous mother and father. Oh, thank you, thank you, darling, so much for all my wonderful life, and I do hope that you will all be happy and successful in India, and that it will be the greatest fun and the greatest triumph for Daddy and for India…… I can’t think of a present to give you. Everyone has given you a farewell present except me, but I don’t know what to give you, and so I will give you my heart. It is going to be very awful for me not having you with me as my castle and my strength, but you know how I love you and how I will try to become a good, wise and strong man while you are away and be worthy of you and all the wonderful things that you have given me”

Antony’s moods were particularly influenced by the weather, and cricket. If it was hot and sunny, he found himself in high spirits. But if the summer was cold and wet, then he descended into fits of depression. Here is an example of one of his depressed moods

“One has to live on one’s own spirits at Eton, and I reckon I’m rather ill tonight. At best my spirits are very low. I miss your letters pouring in almost every day, I Miss your visits and I hate feeling that you aren’t in London, where I can get at you easily. I must say India feels a very long way off tonight and it’s terrible lonesome without you. Once one starts thinking things over everything always seems terribly depressing. One can only get on by just not thinking and my just laughing through every day and only seeing fun and enjoyment. But once my spirits give way I’m right up the pole, and I long for you tonight more than any living soul has ever longed for anybody else in the whole world….”

Cricket bored him, and he played badly. It was speed in sports that most appealed to Antony’s taste, and cricket was too slow for him, and rowing even worse, describing a visit to Henley as “dreary”

“In the first place it is bitterly cold, and the only day in the year when you feel unequal to the river. Then it is terribly crowded by aged men with sombre faces and thin white moustaches, clad in the shortest of shorts which meet nowhere and inadequately cover any portion of their anatomy. They are made of flannel rescued from the dustheap of fifty years ago and worn yearly (without a wash) for fifty-two, which may once have boated the title of white. On their heads they wear caps just too small for them, which when they started their careers had been the pride of their owners….. The racing itself is such as to sicken any heart accustomed to associate racing with speed. To watch the race you manipulate your boat against a cold, wet, slippery pole, to which you cling desperately… then two boats filled with half-naked miserable suffering individuals row past very slowly with a cox in the stern of each trying to excite them by exclaiming at intervals ‘Well done, well rowed, keep it up”

As Antony prepared to leave Eton, he decided to go on Cambridge, even though most of his friends were going to Oxford. In his last letter from Eton, written in July 1922, he wrote to his parents

“How I wish you were here to help me leave this place……I have just taken leave of the headmaster, which was a terrible ordeal. He stood up and shook hands and said, ‘Goodbye, and thank you very much for all you have done’. My God, it nearly killed me, and I don’t feel I have done nearly enough….. Well, then comes Sunday, my last Sunday at Eton – just think of it, It’s a terrible thought, but somehow or other I feel as if I had had my cry, and though speechless with depression I haven’t broken down like I did saying goodbye to Alington. He preached a wonderful sermon in chapel about Eton and leaving and love, and I went to early service in the morning, which was rather awful too. But there is great comfort in prayer and thinking of God, because the whole idea of religion makes one feel how vast the world is and how very small and insignificant little Eton really is…..”

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER V

Oxford: A divided family 1922-1923

By Ann Judge

After leaving Eton, Antony went into the Officer Training Corps, and while staying with Sir James Barrie for a cricket week with a large party of his Eton friends, most of whom were going to Oxford, the feeling came over him that he could not bear to be separated from them when he went to Cambridge. So he wrote to his mother

“However, this is really a party of boys as far as I am concerned, and I love all these wonderful Eton people. I feel quite broken-hearted when I realize that it can never be again. Next year we shall all be men and in two years we shall have forgotten each other…..I feel strangely contented, and yet strangely restless. I find real happiness and friendships that must last for ever, and at the same time I have a deep-rooted, almost subconscious knowledge that it is the meeting-place of two ways – that here in this very house, this very hour, manhood begins and boyhood passes away into a thing of the past…… the real thing that is exciting me at the moment is the possibility of going to Oxford, which is such a wonderful thought that I am intoxicated with anticipation. I have really always wanted Oxford, but my own obstinate nature has hitherto made me stick to Cambridge, and now the moment has come when I have said goodbye to all my Eton friends and I have got to face Cambridge alone – and I suddenly realized I couldn’t”

He continued to write weekly letters to his parents in India telling them about his friends, his social activities, his work, his feelings, his dreams and ambitions, and the books he was reading. The tone of his letters changed with every mood, sometimes gay, sometimes depressed. Although he went to Oxford determined to be happy, and thought at first he was going to be, yet he found the life there very boring at first, and his letters became more discontented.

“Darling, I can’t tell you how queer I feel. I’ve got nothing to do, I feel old & yet not old enough, I feel small & insignificant & not wanted – just part of a dull useless machine which goes on for ever and does no good to anything or anybody. Hopeless is the best word to describe what I’m feeling. I have been reading one or two war books and they make me wish I was just 8 years older. Then everyone knew where he was. He had a definite thing to do…. There’s nothing hanging over me, there’s nothing that I must do. There’s no great work here for me to do. There’s no real pleasure because everything’s pleasure. I just go on from day to day, work, play, joy, sorrow, all mingled into one great indefinable mass of nothingness…..”

Many of Antony’s letters discussed religion, and the meaning of life and his role within it. He has many long, deep philosophical discussions with his parents –

“But I long to go round the world alone to see everyone and everything, how men worked & lived and died. What they care about & lived for – what they killed for & what they were killed for and why? I want to see the real truths of life as I can only lecture them now, and understand the character of man as opposed that that of God… …. As a matter of fact, all this religious discourse doesn’t really explain the peculiar things that I feel. I want an incentive to do something. I have ambition, but no goal & therefore nothing to work for. Money? I want it, but it doesn’t thrill me. God? I don’t understand him & he doesn’t fill me. Passion? Yes, but what does it mean? How do I get it, what do I do? Strength? Yes, but what good is physical strength? Power is perhaps the only light I can see clearly but that is very dim & very far & the obstacles are incredible, and the pleasure which distract one from getting it too good”.

Antony’s fits of depression were always of short duration and the rest of his letters during his first term at Oxford were cheerful enough. His life there was thus summarized in a letter to his sister Hermione:

“This is a very queer place. You can get every type and variety of person and class you can possibly imagine. I only see the best in all of them, so that I long to know all. I feel excited in the political set – ambitious, eager. I feel much the same with the clever people. I love the sporting side – hunting and checks and dogs; and I am slightly ashamed to say that I am terribly happy with the society set…. What a place! No wonder one feels bewildered and at a loose end sometimes…. It’s a great life – a little world all on its own, and just as bewildering and bewitching as the real big world outside”

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER VI

Oxford: University Life 1923-1924

By Ann Judge

As a child, Antony had enjoyed skiing as a pastime, but during the 1923/4 season, he took downhill racing seriously, and competed in the race for the British Ski Championship. During his visit to Murren in January 1924, he wrote –

“Yesterday I won the Kandahar at Murren, and being a bloody fool with a much swollen head and too much ego in my cosmos I have been prevailed upon to come here and go in for the British Ski Championship………….. Tomorrow is the Slalom race, and the day after the Championship race. There are no trains and we have to climb about 3,500-4000 feet and race down, which is unpleasant and almost intolerable. Also there are many good runners to compete with, and I wish I had stayed at Murren, but I always was damned conceited!….. I can’t write. I am too happy. Life is divine. Sun and skiing, it’s all too perfect, but there’s only a week to go now. Oh how I have loved it ….”

He found it impossible to settle back at Oxford, arguing in his letters

“If I’m here for a purpose, what the hell is it, and how do I set about it? But if not, then why, when the only thing that I want to be doing is skiing, am I sitting in my room at Oxford writing to you. By being at Oxford when I might be in Switzerland, am I fulfilling the job which God has given me to do?……. What I really feel is that, if on a pair of skis in Switzerland I forgot everything except the joy of living, and the moment I get back here I sit down and write a long morbid letter on the object of life, Well, why is God’s name not stay on skis?”

But boxing continued to be his main resource, and although the training was irksome, it helped to keep him fit. He was selected to box for Oxford against Cambridge, and though he succeeded in winning his fight, he broke his thumb, keeping it in plaster for a fortnight. Returning to Knebworth for a vacation at the end of April 1924, he wrote to his mother, still in India –

“Here I am in the nursery at Knebworth writing to you. And such a Knebworth too! Bathed in the most glorious sunshine we have seen for years and looking beyond words lovely, as it does in June, although there are no flowers…….. This place has the call of home so much more strongly than even I had ever imagined….. Every now and then one comes up against a very old friend. A picture that one has brushed one’s teeth in front of for centuries! …. The Manor House may one day be a home, but at present Knebworth, and Knebworth alone, has that intoxicating influence on me. I think my heart will break with bliss when I see the last stranger go, and we are all once more united and living here”.

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER VII

Oxford: Coming of Age – 1925

By Ann Judge

Antony is now in his last year at Oxford and getting ready to take his finals. But there was still time to write amusing letters, this one to a friend describing a night he spent under the stars

“ I started back at 10. Just before Slough a man stopped me and said he’d run out of petrol, so I gave him my spare tin, and relieved him of 2/-, which I thought philanthropic! Six miles short of Oxford at 11.35 the car stopped. No petrol! I tried to play the trick the man had played on me with the only two cars that passed, but they both ran me over! The next village was a mile and a half on, the last 2 ½ miles back. So I walked the mile and a half, raised an irate pub-keeper and said ‘Oh pub keeper, some petrol please’. He replied, “Go to hell, you won’t get any in this village”. I threw a brick at him, then walked back to the mote. It then occurred to me that it was the most lovely night God ever made – full moon, not a could in the sky, and very warm. I became romantic and sentimental instead of cross…so I pushed the car into a field and lay down in it and slept all night. It was really wonderful. I don’t believe there has ever been such beauty in England as there was last night. No tropical moon, or bright lights on Broadway, could compare with it. I just gasped at the beauty of it all. Even more wonderful was the early morning.”

Another major event that year was his ‘coming of age’, celebrated on 24 April 1925. There were various celebrations, including this one he describes at Knebworth

“They have all gone to church and left me to pack up my things. I have done all my packing and feel I must write to you. For today I start upon the last course of my Oxford life, as yesterday and the day before I was welcomed upon the first course of manhood by Knebworth. I am acclaimed as being twenty-one, and immediately afterwards I have to start forth upon the last stage of the first effort in my life. I should be an occasion for a glad face and a strong hear, but somehow my heart is heavy and I can only keep on regretting the past. I wish that I had worked harder during this bit and that I had got more done, but the remedy is in the ensuing seven weeks. Then again I feel as if once again I was launching out on my own, when I have a perfect longing for the harbour. I go back to Oxford today and it feels very like the end of my childhood. When we meet again I shall have finished with Oxford and shall be a man……

Last Friday we had a huge luncheon party of the tenants. Mother is sending you the menu I believe, so I need hardly tell you what we had to eat! What no one is all probability will dream of telling you is how extraordinarily charming all your tenants are. I was most extraordinarily touched by the way in which they subscribed to my present and by the sweet way that all behaved & the sweet things they all said. Considering that half of them I have never even set eyes on, I thought it was very sweet of them….

Then yesterday we had a tea party for the village – all the old ladies and young ladies & children, and they all seemed to enjoy it so much. They again said such good & sweet things that I felt it was hard for me to be present. They had a walk in the garden 7 then a cinema. They showed the film of your arrival in Calcutta, which I hadn’t seen before, and I was so excited that I nearly burst. I have seldom enjoyed anything so much or been in such a state of giggles & tears & excitement”

Antony took his degree in History and after leaving Oxford, spent some time with the Lutyens in London before sailing to India to join his parents. He felt none of the sentimental regrets on leaving Oxford that he had expressed on leaving Eton. The cloud of a family separation which had overshadowed these last three years was now passing away and he was now on the threshold of manhood, full of high hopes and joyous expectation.

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER VIII

India: 1925-1927

By Ann Judge

Antony arrived in Darjeeling in October 1925 and spent the next 18 months with his parents. He continued writing letters to his friends, and they beautifully describe his life there. For example,

“Dear Edward – I had always imagined that perfect living was to be found only in P G Wodehouse’s books, and experienced by the very rich in America. I felt that the essential thing about the existence ‘sans reproche’ was Jeeves; that without a flat in London, a range of American expletives, a good cocktail-shaker, a pair of check spats and the inimitable ‘man’, one might as well be contented with an ordinary humdrum existence. I was entirely wrong. The perfect life, the only absolute luxury, is to be found amongst the poor inexplicably raised to the dignity of a Governor of India. I have a divine bearer, black, & with a heavy moustache. He wears a little round black hat, a blue serge frock coat, different coloured trousers every day, no shoes or socks, and he bears somewhat magnificently the name of Lal Bahadur. He is supposed to know English, but his knowledge consists in repeating everything I say, answering every question in the affirmative, lying like a trooper, and doing exactly the opposite of everything he’s told. In England one might feel this to be detrimental to the character of the perfect servant; here it is oddly enough the essence of it! He knows everything, and whatever he does is perfect. He had nothing else to do except to look after me, and he sits outside my room all day. I have also a private man who washes my clothes, and another who irons them. Lal Bahadur dresses me as carefully & perfectly as Molyneux one of his mannequins. My clothes are kept, washed, brushed, ironed, packed with a religious devotion worthy of the followers of the Prophet. My bedroom is the size of an ordinary drawing room, and I have a private bathroom. A man shaves me in bed in the morning before I wake up, so that when I’m called I am quite clean & washed!”

Antony went on various expeditions into the mountains, describing it in another letter to his friend

“I’ve been having the most marvellous time in the maintains, & have crossed right through the Himalayas into Tibet and back over a pass 18,000 ft high, feeling dead ill, eating bovril, sleeping in a tent in 14 sweaters & riding a yak in the day time. Thus it is that we men win through….. So far I have only done the most interesting part of India (ie Sikkim and travelling). It has been quite divine, & so far from tropical extremely cold…. The Governmental idea of camp life & roughing it is rather exceptional. You have 50 servants, a laundry, a horse each, two hot baths a day, a bungalow to live in, 190 coolies, exquisite food, bridge & a private post office! This is abandoned when you get up high. There it is exciting. I didn’t undress for 4 days & one night – slept very coldly in 2 pairs of trousers, stockings & socks, thick vest & pants, a flannel shirt, a jumper (high necked a la Noel Coward) a sweater, a Jaeger coat & an overcoat (blankets excluded).. NB this is quite true.

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER IX

Seeking a profession: 1927-1931

By Ann Judge

In the spring of 1927, at the age of 24, Antony’s chief pre-occupation was to find employment. He recognised the need to make money, but had no taste for the kind of life which money making necessitated. He loved the active, outdoor life, and insisted he had no capacity for business. His first job in a stockbroker’s office was quite distasteful to him – using his position to influence friends to place orders. After 3 months he left to join the Education Department in Conservative Central Office. He wrote home

“I have a palatial office here-I am hampered by the one & only existing report on political activity in the Universities (1925) telling of an almost universal apathy towards politics. My sympathy being altogether with the apathetic undergraduates, I am startling the Central office by suggesting that they are better got at through beer and football than by Conservative Associations. I horrified my chief’s Private Secretary by saying the day of my arrival that the University apathy to politics seemed to me a really healthy sign! He said that he knew he was a fanatic, but he believed that every individual in England should think about & care for nothing else. I told him he needed a long holiday! On the whole I’m afraid that I haven’t started too well”

The following year, 1928, his father then suggested he stand for Parliament, making politics his profession. Antony wrote back

“I feel not sure about it yet, and so want to leave it until after the next Election. It would mean £50 a year less than I get now, but the point is that I want to write. I am going to start trying as soon as I am settled in London, and I don’t want definitely to association myself with any party until I know more. If I wrote under my own name as a Conservative MP, I should have to write the kind of stuff I would be supposed to believe in. I am not sure about it yet, and don’t want to link up irrevocably with the party until I see how the writing goes.

I’m quite happy at this job, which isn’t too dull, is quite well paid, and I think a good political training-ground. I want to do it for a year, try my hand at writing, and if that is a success, plant for it altogether, as it is what amuses me. If it is a failure, well, I am no worse off, and anyway I should have to chuck this job if I was going to stand.”

During the year, Antony moved to a flat in London, accompanied his father on a visit to the League of Nations in Geneva, and then at the end of that year, lost his job. He accepted an invitation to stand for election in the Labour stronghold of Shoreditch, losing the election but gaining some experience of life in a poor London district

“On Monday I dine with Lord Curzon and he is to take me down to the constituency. I suppose they want to vet me before they settle on buying me definitely. If I am passed as sound, I imagine there will be a certain amount of work to be done in the next month or so, and now that it looks so near I funk it!”

The chief event of 1929 was his sister Hermione’s engagement to Mr Cameron Cobbold, and then the wedding which took place the following April 1930 in Knebworth. Later, in June 1930, Antony wrote to his sister

“From now on I expect England to be at its best and loveliest, and the countryside at its most inviting. There will be good summer scents, the hum of bees and the noise of the mowing machine. Everything will grow so big that it seems strange and mysterious, and a little field will become a forest, and every green lane an adventure. Then later on there will be the smell of hay everywhere in the air, and there will be lots of strawberries and cherries and peaches. And all the time the sun will beat down remorselessly. It is a pity that you aren’t still here. But I have a strong feeling that everything is moving on and moving fast. It is not long now and there won’t be a ‘here’ at all. I feel everything has changed and is changing and I don’t like it, but I think I always expected it”

In 1931, Antony was finally elected to parliament, as Member for Hitchin. He also joined the Auxiliary Air Force and started to train as a pilot with the 601 Squadron at Hendon. He wrote to his naturally anxious mother

“You musn’t really mind my doing this for two reasons (a) because it will take an edge off my delight and (b) because you wouldn’t really have it otherwise, for if you only bred sons who stayed at home and gardened you wouldn’t like that. Incidentally, it isn’t any more dangerous than boxing and is good fun and excellent training, and supplies the two missing things in my life – a recreation which I enjoy and a kind of society which I love!”

Later that year Britain came off the Gold Standard, Parliament was dissolved and in October Antony was returned as a national Conservative MP with a majority of 17,000. His party had a huge majority, largely composed on young men, there for the first time. But he was now definitely and successfully launched on a political career.

Knebworth House Archives

LETTERS OF ANTONY LYTTON – CHAPTER X

The last years: 1932-1933

By Ann Judge

As Antony continued his Parliamentary duties, his letters speak volumes about his views of the profession. For example, in January 1932 he wrote to a friend

“Personally I am tired of sitting on his bomb & being not wanted and envied and without security. The whole world is without security of any kind. In the next five years the bomb must either be buried or explode. No one knows which. The majority of people have lost all real interest in the issue & argue ‘anything may happen, let’s make the best of what we have got & know we have got’….

I long for it to be settled one way or another, so that I am either to be satisfied to do my duty in that state of life, etc, and be required to do it, or else may have the change of showing the world that I can do it in another state of life a damned sight better than they!…

I don’t suppose there has ever been such a time in history as this, and no one actually realises it. The fall of the Roman Empire lasted many hundred of years, but our civilisation may collapse in a year. I am not sure I wouldn’t be glad if it did…

So let’s grasp what we can, be thankful for what was good, hope for the future, love, laugh 7 praise, and one day perhaps we shall know….”

And then to his father

“I used to say that the world was divided into two sorts of people – those who see in business, politics and finance high romance and great deeds, and those who see in these things only the same piece of green blotting paper every morning, varied once a week by an efficient Secretary. I am afraid that I belong by nature to the second category, but by training, environment and heredity to the first, so that even if I let Nature have its way, the force of those other influences would be too strong, and I should not be content. But I do feel that in this last year of my young life I have been too serious, and had too much to worry about, with the result that now I can’t honestly feel that anything really matters, and only wish that this much prophesied disastrous world crash would be precipitated. I wish I had been born in time for the War. It would have suited me, and brought me face to face with a physical reality which I don’t feel I shall now ever encounter

My only joy, and indeed my obsession at the moment, is the Air Force, where I get back to the old contentment of school…. I have got more bitten with it even that with skiing, and the summer weather and dreariness of the House of Commons make it seem like good wine to the thirsty and comfort to the wounded….. People say it is a wonderfully interesting time to be living in. Give me a damned boring one then”.

During the summer Antony made many expeditions in his Moth to various parts of the country. He would fly down to Knebworth for the weekends, and land on a very uneven part of the park among the trees near the house. His arrivals and departures always attracted a crowd of admiring schoolchildren, and sometimes he would fly low over the house and church, looping the loop and making wonderful turns in the air, while the villagers gazed and held their breath. At this time, he was also expressing sympathies with Fascism and Catholicism, as shown in this letter to a friend

“I have a new philosophy which started politically & has now spread to religion. I think the whole doctrine of Liberalism which has pervaded and ruled the world since the Renaissance has been one ghastly futile blunder. Of course, like the war, it may have been necessary, and it has surely had its good points. But it is now discredited. I has shot its bolt. And so we are passing it on with an incredible cynical gesture to India & the East. No-one gives a damn now for liberty. He knows he can’t be free anyway. What he wants is work and wages, security, and to be allowed to go about his daily business. He will accept any government that gives him these things and be thankful. This is my new political philosophy. Of course the supreme irony of it is that as the dawn of intellectual enlightenment is breaking over Europe, so in the East, where there has long been a proper understand of these things, the weed of liberty has begun to seed”.

On New Year’s Day 1933, he wrote to his sister

“I have a feeling that 1933 is going to be a year memorable in the life of our country, and of the world, and of our family. It is the high tide – the high tide and the turn of all that is depressing. And the year is going to mark the beginning of a new world, a new light, a great hope, and a great happiness. But it is only a feeling, and had better be left there, with heart in mouth, and a great prayer”

But he only lived for another 4 months. Flying absorbed him more and more. He had moved back to Knebworth, and went to town every morning to work at the Army & Navy Stores (where he was on the Board) and every Sunday he went to Hendon to fly in one of the machines of his squadron. But the day after visiting Knebworth on Sunday 30 April, he left the Stores to take part in a practice formation flight with his squadron in preparation for a special display to be given to the Prince of Wales a week later.

As the squadron was completing a dipping movement over the aerodrome, the leader dived steeply, and maintained the dive so long that all the three leading machines touched the ground. Antony was flying to the left of the leading three and was closely watching the leader – his machine struck a slight rise in the ground with great violence, overturned, and he and his passenger were instantly killed.

His father, Viscount Lytton, writes that his son’s death was in the service of his country, taking all his high hopes and aspirations with him. And that he will be remembered not for what he did, but for what he was.

Knebworth House Archives